Medicine Bundle

Medicine Bundle Colorado Crossfire

Colorado Crossfire The Dragoons 3

The Dragoons 3 The Devil's Bonanza (A Piccadilly Publishing Western Book

The Devil's Bonanza (A Piccadilly Publishing Western Book Gunsmoke at Powder River (The Long-Knives #4)

Gunsmoke at Powder River (The Long-Knives #4) The Long-Knives 6

The Long-Knives 6 The Ghost Dancers (A Crossed Arrows Western Book 2)

The Ghost Dancers (A Crossed Arrows Western Book 2) Colorado Crossfire (A Piccadilly Pulishing Western Book 15)

Colorado Crossfire (A Piccadilly Pulishing Western Book 15) Rocky Mountain Warpath (A Crossed Arrows Western Book 1)

Rocky Mountain Warpath (A Crossed Arrows Western Book 1) Pistolero Justice (A Piccadilly Publishing Western

Pistolero Justice (A Piccadilly Publishing Western Oklahoma Showdown (An Indian Territory Western Book 1)

Oklahoma Showdown (An Indian Territory Western Book 1) Crossed Arrows (A Long-Knives Western Book 1)

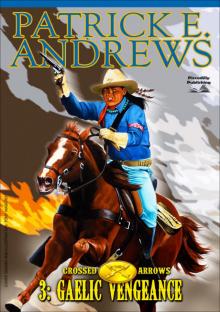

Crossed Arrows (A Long-Knives Western Book 1) Crossed Arrows 3

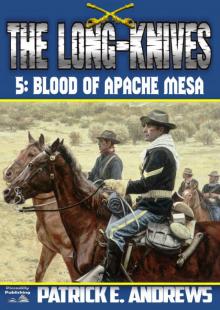

Crossed Arrows 3 Blood of Apache Mesa

Blood of Apache Mesa The Long-Knives 5

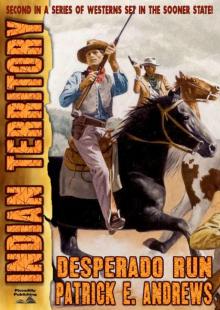

The Long-Knives 5 Desperado Run (An Indian Territory Western Book 2)

Desperado Run (An Indian Territory Western Book 2) Comanchero Blood (A Dragoons Western Book 2)

Comanchero Blood (A Dragoons Western Book 2) The Dragoons 4

The Dragoons 4 Glory's Guidons (The Long-Knives US Cavalry Western Book 3)

Glory's Guidons (The Long-Knives US Cavalry Western Book 3) Indian Territory 3

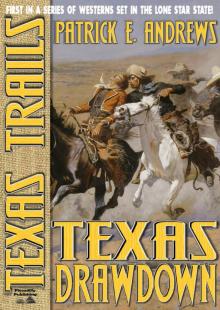

Indian Territory 3 Texas Trails 1

Texas Trails 1