- Home

- Patrick E. Andrews

The Long-Knives 5

The Long-Knives 5 Read online

The Home of Great Western Fiction!

CONTENTS

About Blood of Apache Mesa

Copyright

Dedication

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

About the Author

Wildon Boothe was as innocent as a newborn babe when he lit out for the Arizona frontier. The band-playing military pomp of West Point did nothing to prepare the young shavetail for the man-killing wasteland of Apache Mesa. But if the Army sent him to Hell itself, young Lieutenant Boothe would serve. Life on the range wasn’t exactly going to be easy on his beautiful young wife, either. They’d sworn to stay hitched until death did them part. But with a marauding gang of renegade bandidos on the loose, it could be that they’d be split up sooner than either of them expected!

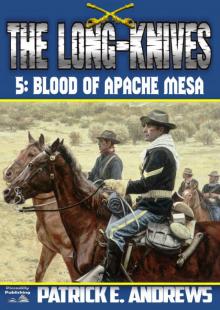

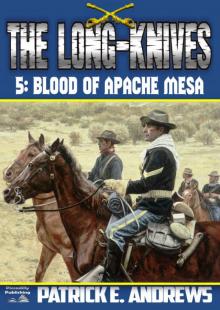

THE LONG-KNIVES 5: BLOOD OF APACHE MESA

By Patrick E. Andrews

First Published by Zebra Books in 1988

Copyright © 1988, 2017 by the Andrews Family Revocable Trust

First Smashwords Edition: August 2017

Names, characters and incidents in this book are fictional, and any resemblance to actual events, locales, organizations, or persons living or dead is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information or storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the author, except where permitted by law.

Our cover features On Patrol, painted by Don Stivers. You can check out more of Don’s work here.

This is a Piccadilly Publishing Book ~*~ Text © Piccadilly Publishing

Series Editor: Ben Bridges

Published by Arrangement with the Author’s Agent.

Dedicated to

Old Sergeants Everywhere

One

Quartermaster Sergeant Tom Mulvaney, working on the regimental property book, looked up when he heard the crate crash to the ground outside. Muttering angrily to himself, the N.C.O. laid his pen down and walked from his office to the warehouse dock. A splintered wooden box lay on the ground, its contents of hardtack spilled out into the dirt.

“All right! Which one o’ you dolts dropped it?” Mulvaney demanded.

The half-dozen soldiers working on the unloading detail looked at the N.C.O. with expressions of angelic innocence.

“Sure now, do you all want a bit of extra duty then?” Mulvaney asked glaring.

Still no one said a word until a grizzled professional private named Dortmann stepped forward. “I done it, Sergeant Mulvaney.” He shrugged. “What the hell difference does it make? You couldn’t bust ’em crackers if you rolled this wagon over ’em.”

“They’re U.S. Army property,” Mulvaney pointed out. “Now get the hammer out of the tool shed and put that box together. Mind you brush the dirt off that hardtack too. There ain’t a post bakery here, so it’s the closest thing to bread we got.”

Fort MacNeil, Texas, was a primitive garrison. One end of the warehouse where Mulvaney and the men worked was also used as the regimental headquarters. It was the only permanent building, having been constructed of lumber laboriously hauled down from the Red River Station.

Mulvaney delayed his return to the office long enough to give a warning look at the others to make sure they fully appreciated his concern for items on the official supply lists. He went back inside once more to devote his attention to the supply document. He’d no sooner settled in to the complicated chore of bringing it up to date when he was interrupted again by noise outside.

“Atten-hut!”

“God!” the sergeant groaned. Now some officer had shown up in the middle of all the work that had to be done. Mulvaney once again went outside to see which ranker had suddenly appeared. He saw young Second Lieutenant Wildon Boothe from L Troop returning Trooper Dortmann’s salute. Boothe was a pleasant-looking, blond youngster with an aristocratic face. The officer glanced up at the dock and saw Mulvaney. “Good afternoon, Sergeant.”

“Good afternoon, sir. Is there something I could be doing for you?”

Boothe stepped up onto the dock. “Yes. I’ve come to see about drawing some furniture for my quarters.” He had only recently arrived in the regiment and had been billeted with the other bachelor subalterns in their dormitory-like quarters at the end of officers’ row.

“Ah, yes, sir,” Mulvaney said, suddenly remembering. “Your missus will be joining you soon.”

“That’s right,” Boothe said. “I have to set up suitable quarters before she gets here.”

“Well, not to worry, sir,” Mulvaney assured him. “We have some things you can put to good use.”

It wasn’t army policy to provide furnishings for officers, but on the frontier special provisions had been made due to the difficulty of transportation and purchase of new household items. Officers newly assigned or on temporary duty could be provided for from the quartermaster stores when the necessary things were available.

The sergeant led Boothe toward the rear of the building. They stepped in a corner of the warehouse where some miscellaneous pieces of furniture were stacked. “Not bad, hey, sir?”

Boothe said nothing. There was a battered wooden table, some unmatched straight chairs, a bed that looked as though it had been handmade, and some shelves that also seemed to have been banged together from used boards. “This is all you have?” he asked.

“Yes, sir,” Mulvaney answered. “And it’s plenty grand for two people.”

“Where did this come from?” Boothe asked, clearly disappointed.

“Why from that ranch family that was killed by the Indians last spring,” Mulvaney said, confused by the young officer’s apparent lack of enthusiasm. “We tried to find their next-of-kin, but it was impossible. So the poor folks’ belongings became the official property of the army.”

“I suppose it will have to do until we can order some of our own,” Boothe said.

“I’ve got a detail outside unloading wagons now, sir,” Mulvaney said. “I’ll have ’em tote the goods over to your new quarters.”

“Yes, thank you,” Boothe said. “I shall meet them there, Sergeant.”

Mulvaney opened the front door for the officer. “Now don’t you worry none, Lieutenant Boothe. Your bride is gonna love the stuff. Why, it’s a grand way to start out an army marriage.” He let Boothe out, then walked back to the rear of the loading dock. He stopped outside. “Dortmann! Get these lads up here. You’ve some lovely furniture to carry over to Lieutenant Boothe’s new quarters.”

“Can we use the wagon, Sergeant?” Trooper Dortmann asked.

“And put extra use on it? No!” Mulvaney barked. Dortmann grinned and pointed to his boots. “We’ll wear our footgear out.”

“I might have you do it barefoot, bucko!” Mulvaney snapped. “Now get up here!”

While the soldiers prepared to transport the furniture, Boothe walked across the post to his new quarters. He looked at the small house made of sod blocks. Although the window frames were wood and had glass in them, the roof was no more than a tarpaulin especially cut for its function. Sighing inwardly, he opened the door. Even though it had been freshly swept and dusted, it still looked like the insid

e of a large, empty henhouse to him.

~*~

It was the autumn of 1883, and the year had been an exciting one for Second Lieutenant Wildon Boothe of the United States Cavalry. That spring the young scion of a wealthy upstate New York family had graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point to fulfill a lifelong dream.

Wildon had always wanted to be a soldier. An uncle had raised a volunteer infantry regiment to serve the Union cause during the Civil War at about the time Wildon was born. As the youngster grew up, he was regaled with tales of glory about fierce battles in such places as Manassas, Antietam, and Gettysburg. Even after the war the uncle maintained his service in the state militia, and Wildon loved to be allowed to attend muster days when the part-time soldiers gathered for parades, drills, and camping in tents at the Catskill military reservation. When he was twelve, he was given a gift that was to be the favorite of his boyhood: a cut-down uniform just like the ones the militiamen wore.

The boy’s other valued playthings were his toy soldiers, wooden rifles, and other martial toys. As he grew older, books on military subjects and wars became an obsession with him. No one was surprised when he asked his uncle’s aid in procuring a congressional appointment to West Point.

In his later teens, before attending the academy, two more interests appeared in his life. An active, athletic youngster in spite of his slim build, he loved horseback riding and hunting. The two pastimes were a passion with him, and he developed into a skilled equestrian and a dead shot.

Horseback riding, however, introduced the young man to an even deeper preoccupation. This was Hester Bristol. Three years younger than Wildon, she was the heiress of the Bristol Soap fortune and came from a family as socially prominent as Wildon’s. She, too, loved to ride. Hating the constrictions of sidesaddles, she was known to impetuously mount a horse with a regular saddle and gallop, with stockinged legs showing above her boots, across the rolling terrain to take jumps over fences, creeks, and other obstacles. Actually, she and Wildon had known each other as small children, but only when they were older did they develop any real affection, which manifested itself through their common interest in horses. Later, those feelings became romantic and loving, and Wildon’s awkward attentions at dances and parties evolved into serious courtship. The evening before he left for West Point, their engagement was announced.

A month after Wildon’s graduation from the military academy, they were married in one of the season’s most prominent weddings at Hester’s family estate on Lake Champlain. After a short honeymoon at Niagara Falls, the young couple was separated while the brand-new second lieutenant went west to join his cavalry regiment at Fort MacNeil in central Texas. The plan was for Hester to wait at her family’s home until he had managed to settle in and could send for her. Neither of the young people realized what was in store for them out in the desolate frontier country.

Wildon knew the cavalry forts were not elegant, unlike the Eastern garrisons. He had heard a bit from soldiers who had served in the West, and an occasional officer detached from a frontier unit would be assigned to West Point as an instructor. Yet he still did not fully appreciate the tough conditions endured by soldiers in the Indian campaigns. He thought it would be rather like the militia camps with a few tents and perhaps with well-constructed frame buildings.

Hester, on the other hand, was in complete ignorance of the army’s situation. The only military post she had ever seen was West Point during visits with her mother to see Wildon. In her mind, all garrisons were constructed of gray granite buildings and well-kept green parade grounds within the dignified protection of stone walls.

When Wildon arrived at Fort MacNeil, he was appalled at what he saw. The officers’ quarters were no more than sod huts with canvas roofs. They were filthy, insect-infested, and crude beyond imagination, and he had stared at them in near shock. A dearth of building materials made it impossible to build anything better.

He was also unpleasantly surprised at the enlisted men he soon commanded. A large percentage were foreign-born, including a few who could hardly understand English. Many of the Americans were rejects from society with tendencies toward crime, dirtiness, and insubordination. Others were naive youngsters looking for adventure, who soon had such boyish ideas pushed out of their heads by endless drill, hard physical labor, and the unbelievable tedium of being stationed far from any of civilization’s amenities and pleasures.

The noncommissioned officers included brutes who kept order and discipline through painful physical punishments, kicks and beatings, and abject fear. Wildon was quick to learn that this kind of sergeant and corporal was necessary to keep the majority of troopers under any kind of control.

But the one thing that the socially segregated officers, noncommissioned officers, and soldiers all shared in common was a marked tendency to drink strong liquor in large quantities. Drunkenness was everywhere to an extent that shocked a properly raised New Englander from a wealthy, cultured, and socially conscious family.

Yet Wildon’s love of soldiering was such that he quickly adapted to the situation. He was a young man with a hard, realistic way of looking at things. The army wasn’t supposed to be a soft life, and even his uncle had warned him that enlisted men in the regular army were certainly not like the citizen-soldiers of the militia. It was a tough job requiring tough men. In order to be a good officer, Wildon would be expected to endure unpleasantness and inconvenience in both garrison and the field with the same fortitude he would be required to display toward danger in war. His healthy emotional outlook helped him to accept the hard realities of the Regular Army as a challenge. Within a few weeks he had settled in quite well.

One other aspect of the life at the desolate garrison—besides the martial pomp and ceremony—Wildon found to his complete liking: plenty of opportunity for hunting on the wild prairie. Game in the form of buffalo, antelope, elk, and deer were abundant. Wildon never missed a chance to join a group of fellow officers for a shooting trip to bag fresh game for the mess halls. He even followed his companions’ example by purchasing a buckskin outfit complete with broad-brimmed hat for the pastime.

But Wildon knew such recreation would not amuse Hester. After some long, serious thought, he decided that the blunt truth was the best course to follow. He wrote Hester a painfully detailed description of Fort MacNeil. He told of the officers’ quarters, the soldiers, the hard drinking, and even of the several uncouth characters in the officer cadre. He sent the letter with the full realization that his beloved might decide to stay back in New York or insist that he leave the army and return home to her.

But Hester’s reaction surprised him. She responded to the letter with a girlish, romantic reply saying she would go anywhere her true love must go. She even added an innocent postscript saying she thought the whole affair would be a wonderful and grand adventure.

Wildon knew that attitude would be dashed to pieces within the first five minutes she spent at Fort MacNeil.

Trooper Dortmann banged on the door. “Sir! We’re here with the furniture.”

“Yes. Come in,” Wildon responded.

“Any place in particular you want it?” Dortmann asked as he and the others struggled into the small room.

Wildon looked around. “The tables and chairs can stay in here. Take the bed and those shelves into the other room.”

It didn’t take the soldiers long to put the sparse furnishings into place. Dortmann, who was the senior private present, was a member of Wildon’s troop. “There you are, sir. All settled in.”

“Yes, thank you. Dismissed. But I would like a word with you, Trooper Dortmann,” Wildon said. “Yes, sir.”

The young officer waited for the others to go outside. “You’re a veteran soldier, aren’t you?”

“Ten years of service, sir.”

“A man with your experience would serve the army better as a noncommissioned officer,” Wildon said bluntly. “I would recommend that you apply yourself a bit harder to earn some che

vrons for your sleeves.”

“No, thank you, sir,” Dortmann replied cheerfully. “I like being a private soljer, sir. In all this time, I’ve never had as much as a lance jack’s stripes to boast of. And I like it that way.”

“I see,” Wildon said. “Very well. You’re dismissed.” He realized his uncle had been entirely correct. There were types of soldiers in the Regular Army that would never be found in a gentleman’s militia regiment. He was disappointed in Dortmann, but his more pressing problems came back to mind once more.

Turning around, Wildon could see that the place actually looked worse with the awful table and chairs. He walked over and sat down in one of them, knowing that the first crisis in his marriage would begin the instant Hester walked into their new home.

Two

A balmy breeze wafted off Lake Champlain, rippling the silk curtains as it made its way with gentle persistence to float through the room. The sweet smells it gathered off the garden added to the pleasure of the early afternoon’s warmth.

Hester Bristol Boothe, wife of Second Lieutenant Wildon Boothe, turned from the open window and looked at her cousin Penelope and sister Fionna. Both were gently repacking her things into the large hope chest. Hester was a small young woman of eighteen years, trim and graceful, her long brown tresses held in place with a silver comb. Slightly freckled across the bridge of her small nose, she had laughing green eyes and a full mouth that smiled easily.

“I can’t believe it,” Hester said. “It seems so unreal now that I’m leaving.”

She looked once again out across the rose garden. These were the Ellsworth variety. Her father took so much pride in them that he wouldn’t permit even the family gardener to touch his beloved plants. The flowers grew abundantly and beautifully in the late summer sunshine. This fragrant area was tucked in behind a high brick wall. From that point, a well-cared-for lawn sloped down toward the lakeshore.

Penelope looked up at Hester. “Why don’t you stop gawking out the window and help us?”

Medicine Bundle

Medicine Bundle Colorado Crossfire

Colorado Crossfire The Dragoons 3

The Dragoons 3 The Devil's Bonanza (A Piccadilly Publishing Western Book

The Devil's Bonanza (A Piccadilly Publishing Western Book Gunsmoke at Powder River (The Long-Knives #4)

Gunsmoke at Powder River (The Long-Knives #4) The Long-Knives 6

The Long-Knives 6 The Ghost Dancers (A Crossed Arrows Western Book 2)

The Ghost Dancers (A Crossed Arrows Western Book 2) Colorado Crossfire (A Piccadilly Pulishing Western Book 15)

Colorado Crossfire (A Piccadilly Pulishing Western Book 15) Rocky Mountain Warpath (A Crossed Arrows Western Book 1)

Rocky Mountain Warpath (A Crossed Arrows Western Book 1) Pistolero Justice (A Piccadilly Publishing Western

Pistolero Justice (A Piccadilly Publishing Western Oklahoma Showdown (An Indian Territory Western Book 1)

Oklahoma Showdown (An Indian Territory Western Book 1) Crossed Arrows (A Long-Knives Western Book 1)

Crossed Arrows (A Long-Knives Western Book 1) Crossed Arrows 3

Crossed Arrows 3 Blood of Apache Mesa

Blood of Apache Mesa The Long-Knives 5

The Long-Knives 5 Desperado Run (An Indian Territory Western Book 2)

Desperado Run (An Indian Territory Western Book 2) Comanchero Blood (A Dragoons Western Book 2)

Comanchero Blood (A Dragoons Western Book 2) The Dragoons 4

The Dragoons 4 Glory's Guidons (The Long-Knives US Cavalry Western Book 3)

Glory's Guidons (The Long-Knives US Cavalry Western Book 3) Indian Territory 3

Indian Territory 3 Texas Trails 1

Texas Trails 1